In 2016 I got my Ph.D in neuroscience. My thesis focused on perceptual learning, asking where exactly in the brain does perceptual learning take place, how might training paradigms affect the learning effect, and whether/how learning generalizes to novel conditions. We discuss “learning” in a basic science framework, but unarguably, understanding “learning” has its significance for application.

One year before my graduation, I started to think about which labs I want to apply for postdoc position. One critical big picture question is: do I want to pursue basic science or translational science? It didn’t take me too long to apply and get accepted into Dr. Gordon Legge’s world-renowned Low Vision Research Lab. In my colleagues’ warm farewell greetings of “enjoy ice-fishing”, I arrived in the Twin-Cities to start my low vision research.

The Question.

At the beginning of my postdoc years, I worked my head off to have a “smooth” transition — start projects ASAP and keep a good record of manuscripts. Now its been four years, but I found myself started to frequently ask the question: where does my research stand in the vision rehabilitation field?

The First Answer

My answer to this question was once negative. As a behavior science researcher, I am too far from the front line and know too little about the war. Ophthalmologists diagnose eye diseases, help slowing down the vision deterioration, and endeavor to cure the diseases by research. Therapists teach the patients how to manage everyday life and regain independency by hands-on training. I once lost my tongue when an ophthalmologist told me “you are asking a black-and-white question”. I was helpless when my vision therapist friends commented that “but everybody is different”. In stead of justifying for “finding group averages”, I wrote on the first page of my yellow notebook: “Rule of thumb #1: Always be aware of individual differences.”

The Road to A New Answer

I started to perceive this question differently after I had put both feet in the rehab field. In 2019 I was awarded the Envision Fellowship, and started working with Dr. Don Fletcher in his Envision low vision clinic as part of my training. Dr. Fletcher is an ophthalmologist who is interested in vision functions and behavior research, he is also one of the first clinicians who started an integrated vision rehab approach. In Dr. Fletcher’s practice, he conducts vision assessment for the patients, and works with the occupational therapists and orientation&mobility specialists to design rehabilitation plans. I thus got the opportunity to peep into the realm of vision rehabilitation.

I started to feel that what I have learnt as a behavior researcher can be of great use in the vision rehab world. I grab Dr. Fletcher in his breaks to ask about my observations in the sessions, sometimes I got the explanations and sometimes I got “that’s a good question, you should research into that”. I followed Andra, the occupational therapist, in the home-visits and worked with her to look into the generalization of reading training to recognizing faces. I discussed with Laura, the orientation&mobility specialist, about the difficulties of walking a straight-line (i.e. veering) in her patients, and found that her anecdotal observation is highly consistent with my project hypothesis.

A Map for the Lost (Me)

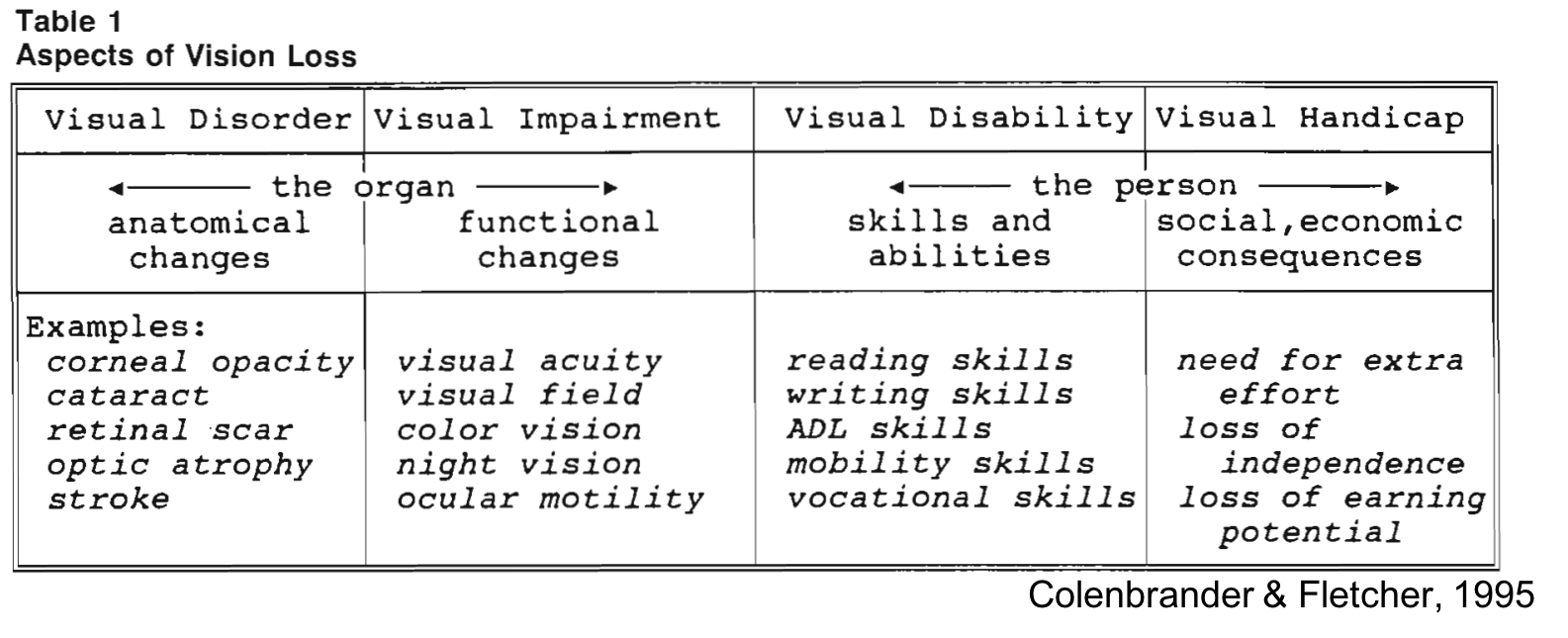

More importantly, I found the map that can help me locate myself when I am frustrated or fall in the episodes of “Imposter Syndrome”. Table 1 shows “four aspects of vision loss”, summarized by Dr. Fletcher and his mentor Dr. Colenbrander. The four aspects include visual disorder, visual impairment, visual disability, and visual handicap. Let’s understand these four aspects using an example.

Example:

Mr. Carrot was diagnosed with age-related macular degeneration (AMD). AMD is an eye condition that primarily affect the center of the eye ball — the change in the eyes is the visual disorder. Mr. Carrot complains that reading is becoming more and more difficult — such functional change is the visual impairment. Mr. Carrot’ enrolled in vision rehabilitation training to learn how to read better with vision skills and how to optimize the lighting in his study, which has greatly improved his visual ability. Mr. Carrot does not feel handicapped because of his vision. He is very activate in the local low-vision community, and recently he is working on a series of “vision awareness” events to make more people understand low vision.

Where I stand.

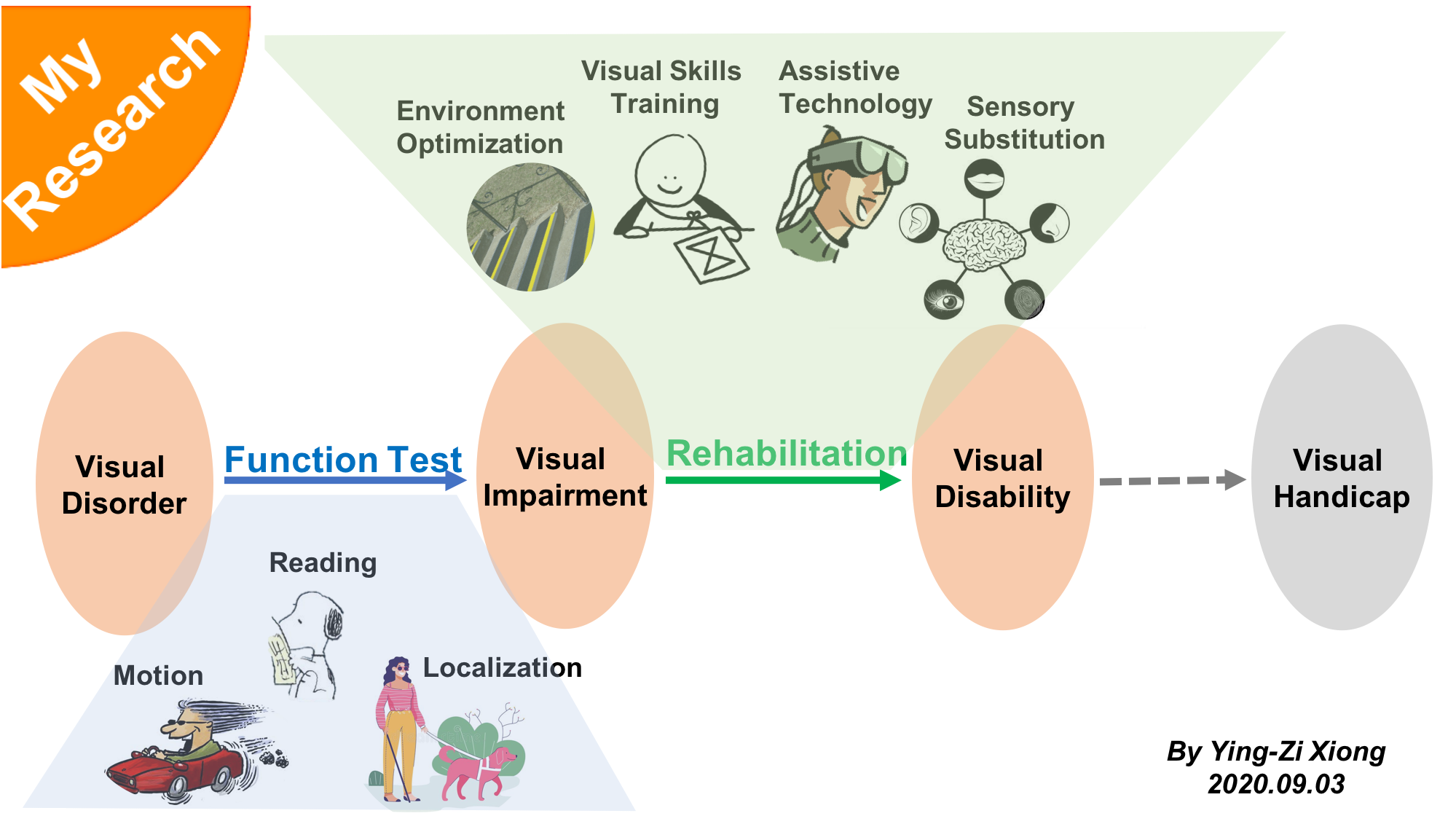

In Figure 1, I put my research topics as landmarks on the “map”.

From visual disorder to visual impairment, my research can contribute to the visual functional assessment. For example, in one of my ongoing studies, I designed a functional spatial localization task to help orientation&mobility therapists in the assessment of their patients. The face recognition test that I designed in collaboration with the occupational therapists in Envision Low Vision Clinic also lands in this category.

From visual impairment to visual disability, my research explores rehabilitation strategies to help the patients make the most use of their residual vision. For example, my colleagues and I investigated how to determine the dimensions of optimal reading devices to help people with low vision achieve efficient reading. I am also developing training methods to help people with dual sensory loss optimally integrate their residual senses in the complex environment.

Figure 1. My research on the map.

Finding my position in the field really helps me in navigating my career path. Now I can more confidently introduce my research to people in and outside the research field; and I am also clearer about my strengths that I can bring to a collaborative team and my weaknesses that I need to learn from the collaborators.

In July 2020 I got an invite from Prof. Steve Engle to make a video clip to describe what I am doing in my career, and how I am using my knowledge of vision science in my work. In the video I shared the perspectives and opinions that I have described in this blog. I enjoyed making the video, but I think my oral English is actually slightly better than in the video :P. (Click to see the video).